Climate and politics in emerging markets

Governments in Asia and Africa lead the emerging world in their ‘Commitment on Climate’

The political impacts of climate stress

The country’s current administration’s commitment to emissions reduction

The country’s policies regarding renewables energy investment

The role of ‘green’ political parties or grass-roots environmental movements.

We also asked the contributors to assign a rating for each country on the current government’s ‘Commitment on Climate Policy’ using a simple 1 to 5 scale. A country rated 5 would prioritise climate above most other policy objectives, while a country rated 1 would give almost no consideration to climate objectives when making policy.

'Commitment on Climate' ratings key:

Some caveats to note: most importantly, our rating is subjective. We asked Oxford Analytica’s contributors to provide their personal view on the degree to which the serving government was committed to reaching climate policy goals, not an objective assessment of, for instance, the country’s targets for emissions or the share of renewables in the energy-generation mix.

We should also note the expert contributors providing these ratings are political analysts rather than climate policy experts, and that inter-rater reliability is often a problem for such subjective assessments. Some contributors gave countries the benefit of the doubt. For example, China is among the world’s largest emitters and Saudi Arabia among the largest fossil fuel exporters, but both governments have recently adopted ambitious climate policy programmes and our contributors therefore gave them better ratings than one might have anticipated. For Qatar, by contrast, despite a commitment to host a ‘climate neutral’ World Cup, our contributor was more skeptical. As to which of these subjective estimates will prove correct, only time will tell.

Those caveats aside, the climate and politics ratings in the 61 profiles did produce interesting results, which we were able to assess statistically. We review the results of this statistical analysis below.

Commitment on climate rating

What drives commitment on climate policy?

Vulnerability – in emerging market countries facing a clear threat from the impacts of climate change, governments appear to show a greater commitment on climate policyState capacity – countries with a more effective civil service appear to show a greater commitment on climateOil and gas rents – countries that earn more from fossil fuel exports appear to be less likely to commit to strong climate policies.

We also expected that a fourth factor, politics, would play an important role, although we were unable to find statistical evidence for this view. Below, we consider this factor as a possible explanation for certain outliers and examine the three key factors in more detail.

Commitment on Climate Ratings and Possible Drivers

Commitment on Climate Ratings and Possible Drivers

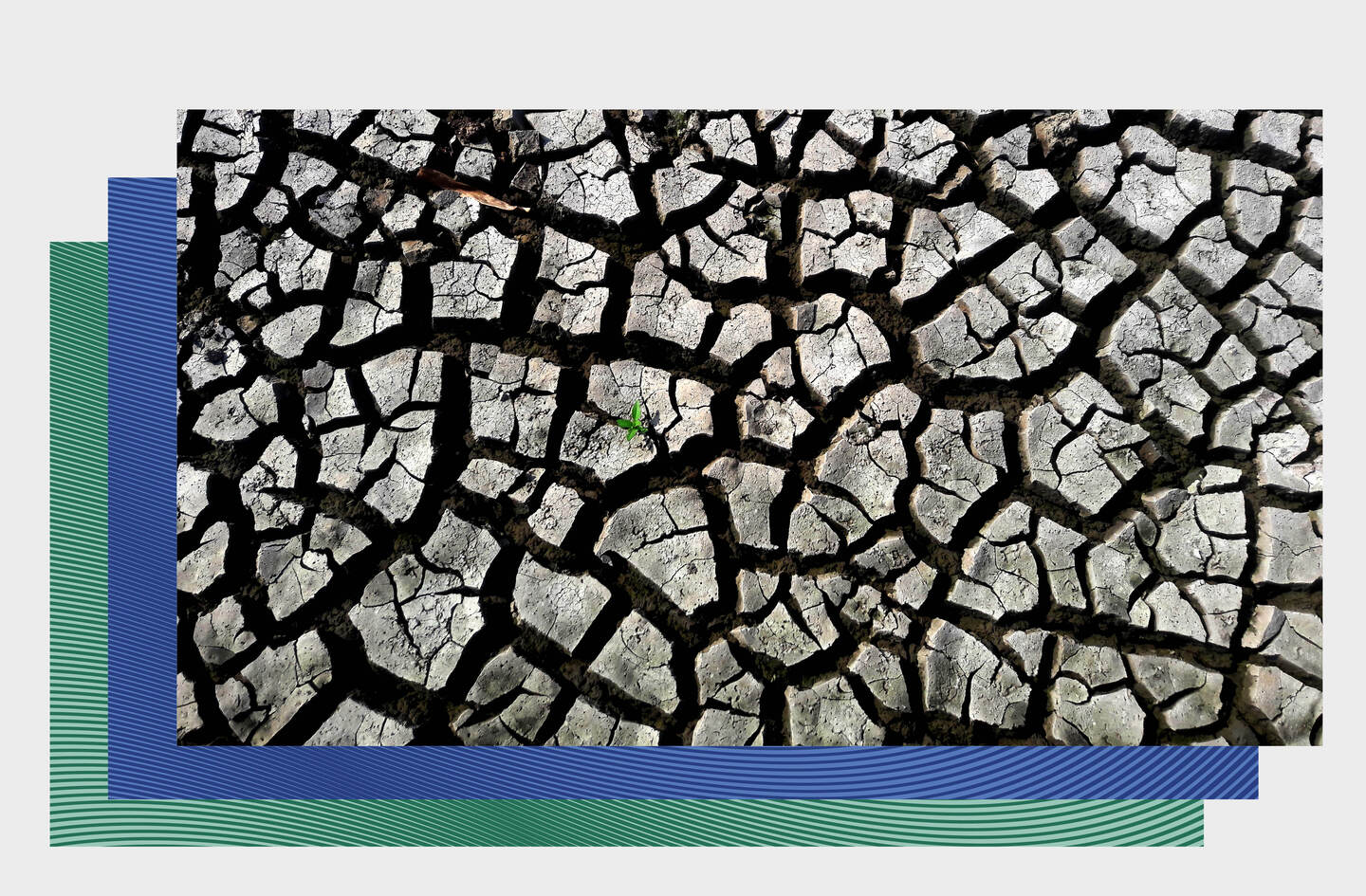

Vulnerability

Many of the countries in the WTW Political Risk Index count among the world’s most vulnerable on mutiple such indicators. Bangladesh, for instance, was already estimated to have experienced annual losses linked to adverse climate events averaging nearly 2% of gross domestic product between 1990 and 2008. It has also been projected to lose almost a tenth of its land mass to rising sea levels by 2100. The Philippines, meanwhile, ranks among the top three countries in the world in terms of population exposure to climate-related hazards.

In some countries, climate issues are contributing to political instability. Our contributor for the Central African Republic writes: “Climate change … has some connection to the drivers of the conflicts that have plagued the country for more than a decade,” as shifting weather patterns alter grazing conditions and thus pastoralist movement patterns (for more detail, see its country profile found in this document).

We tested a number of indices of climate vulnerability, but had the greatest success in identifying statistical relationships between our contributor’s Commitment on Climate ratings and the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) indicators. In particular, the ‘human habitat’ indictor, which measures the projected impact of floods, heat waves and other extreme weather events on cities, and the ‘food and agriculture’ indicator, which measures the potential for food insecurity due to changed precipitation and temperature patterns, appear to have a robust and significant link to Commitment on Climate.

For many emerging market countries, the human and economic costs of climate change are projected to be severe. For some, such as the Philippines and Bangladesh, these impacts are already being felt. It stands to reason that governments in these countries would be motivated to protect their populations from these rising costs.

Countries with effective governments ten to rate higher on 'commitment on climate'

State capacity

Of course, it should be noted most of these poorly governed countries, in part due to low levels of economic development, tend to emit little carbon, either on a per capita or aggregate basis. Even limited action by, for instance, the U.S., would have a drastically greater impact on world emissions than almost anything these countries might conceivably do. The entire continent of Africa, for instance, accounts for only around 3% of global carbon emissions.

We tested a number of indicators of governance quality but the strongest statistical relationship we found was between the Worldwide Governance Indicators’ ‘government effectiveness’ score and our contributors’ ratings. This score combines subjective and objective indicators of public service quality, civil service performance, and the quality of high-level policymaking.https://ccpi.org/ ). On that index, China again scores well, but Malaysia does not.

Oil and gas rents

Indeed, it is difficult to find any emerging market government that has significantly gone against its short-term economic interests as a fossil fuel producer to take a strong stance on climate. In our Index, there is one possible case: Saudi Arabia, which earns a 3 out of 5, based on ambitious green investment plans. Even this middle-of-the-road rating is a triumph of hope over experience as the kingdom is currently the world’s fourth largest consumer of oil and gas liquids.

Politics

One topical example is subsidies. In many emerging market countries, governments subsidise prices for staple goods such as food and fuel. These subsidies are often popular in good times, but in hard times can put the government in the awkward position of being held politically responsible for increases in prices. Bread riots may sound archaic (often said to be one cause of the French Revolution), but when the bread price is set by the government, joining mass protests against rising prices makes sense.

This dynamic presents governments with an awkward choice when global food and fuel prices rise, as has been the case recently. The government can either allow the domestic price to rise accordingly or increase subsidy payments to keep the price down. The first choice threatens to trigger political unrest, while the second choice threatens to imperil the country’s fiscal position.

The stakes are high. Unrest in Kazakhstan in autumn 2021, for instance, was ignited by fuel price increases. More recently, in Sri Lanka, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has recommended replacing fuel subsidies with basic income payments. Fuel subsidies not only incentivise greater consumption of fossil fuels, to the detriment of the climate, but such subsidies are also poorly targeted as a means of alleviating poverty. Perhaps predictably, however, the Sri Lankan government’s efforts to rein in subsidies have contributed to dramatic popular protests.

Especially in democracies, other political factors that might play a role in deciding Commitment on Climate include the platforms of politicians and grass-roots environmental movements. In Chile, for instance, a new left-leaning government has made a green recovery a centerpiece of its political platform and scores a 4 on our 5-point scale. However, in Brazil, by contrast, the current government actively downplays climate and environmental issues and the country rates a 2.

Grass-roots politics may also play a role. For instance, in 2017 Kenya became one of the first countries in the world to ban plastic bags, in part because of the Green Belt Movement led by the late Nobel Prize winner, Wangari Maathai. In Thailand, environmental non-governmental groups have been active for decades. Even in times of martial law, the Thai government has been reluctant to censure or otherwise constrain environmental advocates.

But such grass roots movements appear, so far, to have had a limited impact on climate policy in the emerging world. With the usual caveats about possible error in our ratings, factors such as fossil fuel revenues, state capacity, and vulnerability to climate impacts appear to have the clearest impact on climate policy, regardless of whether a country is a dictatorship or democracy and irrespective of pressure from advocates or the political biases of the serving administration.

Regional averages on commitment on climate and possible drivers

A review of the global league tables

Some of these top-rated countries, particularly Malaysia and Chile, are known for unusually strong governance when compared to other emerging economies.

Senegal is an unusual member of the list in terms of level of development. The country’s per capita income of roughly $1,500 per year is a fraction of Malaysia’s or Chile’s, which stand closer to $15,000, but that low level of development can, in a sense, be an advantage. New solar power plants and electric rail lines are first and foremost much-needed additions to infrastructure in a country where roughly a quarter of the population lacks regular access to electric power. Partly as a result, the government of Senegal “gives as high a priority as is realistically feasible to renewables and protection of the environment and fighting desertification,” Oxford Analytica’s expert contributor writes.

At the other end of the spectrum, three countries – Libya, Myanmar, and Turkmenistan – are rated at 1. Both Libya and Myanmar are preoccupied by political crises. Turkmenistan’s rating may be read as somewhat harsh, given its pledge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from 2030. This is better than many other countries with better ratings, some of which have refused to set formal targets.

But Turkmenistan is also in crisis, albeit one of a subtler nature. Oxford Analytica’s expert contributor writes: “When in 2020 China cut its imports of natural gas from Turkmenistan, the country’s economy experienced a severe downturn,” which contributed to social unrest. Hence, the government has had little attention to spare for the country’s aging oil and gas infrastructure, and was, according to one study, the fourth largest producer of methane in the world.

Looking across world regions, governments in Africa and Asia lead the emerging world on Commitment on Climate. On a regional-average basis, Asia’s strength is government effectiveness. Asian countries tend to have strong policymaking and effective bureaucracies capable of carrying out political goals. Exemplars are Malaysia and China, which our contributors rated highly on the strength of their well-developed climate transformation plans, as opposed to their track records.

By contrast, Africa’s ‘strength’, in a manner of speaking, is the acute danger climate change poses to its people. Again, on a regional-average basis, threats from desertification, sea level rise and climate-related extreme weather substantially exceed the rest of the emerging world, which may be a factor motivating African governments to act.

And yet, even taking this motivation into account, many African countries are rated above where our statistical model would predict, including Cameroon, Central African Republic, the D.R.C., Ethiopia, Morocco, Mozambique, Uganda, and top-rated Senegal. A cynic might note that because of their low level of development, many of these African countries expect international donors to fund their climate programmes and are therefore committing little money themselves. An optimist, however, might hope these commitments by African leaders will show the way for the rest of the world.

2020 carbon emissions vs commitment on climate

Assessing global impacts

That said, we conclude with a chart that attempts to assess the global implications of our analysis. Only one country appears in the ‘red box’ of high emissions and low Commitment on Climate: Russia. Two others straddle the midpoint: China and India, both of which would appear off the top of the graph in terms of volume of carbon emissions, and both of which score a middling 3 on our expert rating. Many countries, including Malaysia and several African nations, are well-placed in the ‘green box’ of low contribution to world emissions and, despite that, a strong Commitment on Climate.

Most of the countries in the Index, however, fall into, or on the edges of, one of the ‘yellow boxes’: low Commitment on Climate, and low emissions (by global standards). Thinking in terms of global climate impacts, that is arguably an acceptable status. In the future, of course, as these countries develop, if their Commitment on Climate remains low, their emissions are likely to rise, and, they will – like Russia today – pose more of an obstacle to global efforts to combat climate change.

Statistical appendix (http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/), the sum of oil rents and natural gas rents (as a percentage of GDP) from the World Bank World Development Indicators (https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators), and two indicators from the Notre Dame Climate Adaptation Initiative, ‘Food’ and ‘Human Habitat’ (https://gain.nd.edu/).

Note that multicollinearity may impact our results. The highest correlations are between government effectiveness and human habitat, at 0.42, and between government effectiveness and oil and gas rents, at 0.27.

Results are presented here for logit regression, which may be more appropriate for our Commitment to Climate rating: